Part 2: The Jazz Players of the Evaluation World: Responding to Systems-Change and Place-Based Evaluation Challenges.

August 21, 2020 / Edited by Kaisha Crupi

August 21, 2020 / Edited by Kaisha Crupi

In our last article, we talked with co-creators of Australia’s first Place-Based Evaluation Framework, Jess Dart and Ellise Barkley, along with systems-change expert Anna Powell about the unique challenges these approaches present. In this week’s instalment, we’ll be discussing practical techniques and tips for navigating evaluation in this emerging field, including how to make sure everyone’s on the same songsheet (even if we’re all playing different notes!).

A key challenge raised was the long-term nature of systems change and place-based approaches – and managing expectations around this. What advice do you have?

“I find it helps to use a phased theory of change.”

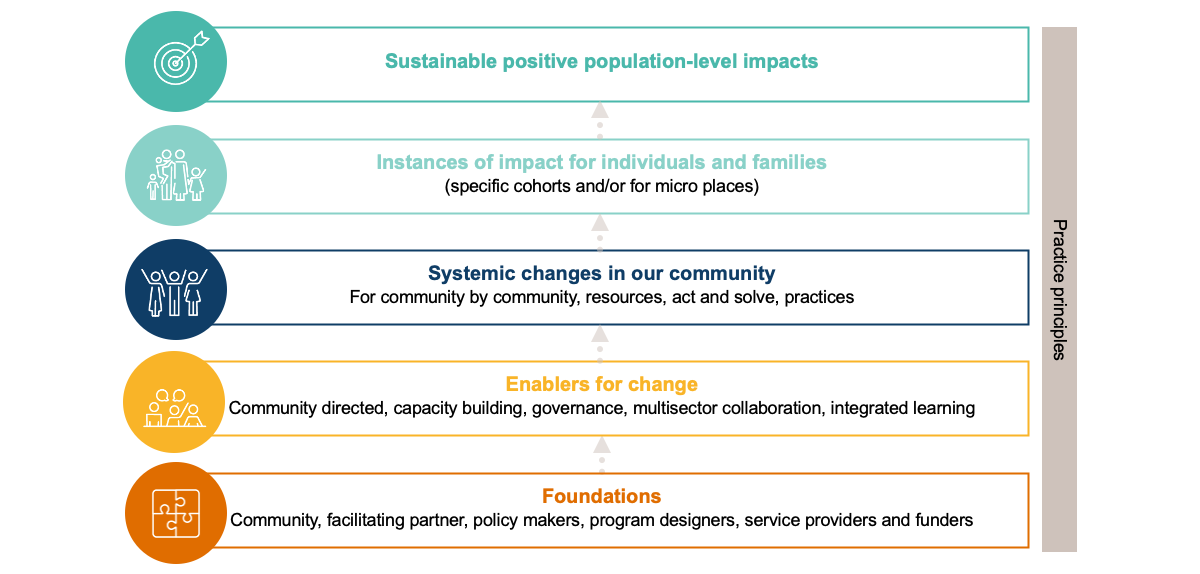

By “phased”, I mean that the theory of change includes a number of different “levels” of change – below is a generic one that we use in the framework to give people an understanding of this. So, while we all want to see and measure population-level change, we need to accept that it often takes many years to achieve, and that we will need to measure at more than one level of change.

The next step is to use this phased theory of change to chunk out your measurement plans. For example, in an initiative in the early stages of implementation, your measurement might simply focus on developing a baseline of population level change and also examining whether the conditions for change are being established. At three years in, your measurement and evaluation plan might also start to look at systems changes, and emerging instances of impact for families. It might not be until year six that you start really looking into the effects of the systems change on broader trends.

Your role as an evaluator is to educate your stakeholders about what to expect to see over these different phases. You need to manage people’s expectations for the sorts of results they are likely to see early on, and really hammer home the point that there are not going to be population changes for many years.

“This approach also helps address another key challenge – that systems and place-based change is complex, multi-dimensional and non-linear.”

Therefore, the ways we measure progress need to reflect this. In this context, progress is both about how initiatives are travelling towards their broader goal as well as about building the enabling conditions for longer term change. Because it’s not a linear process from A to B – there can be iterations of progress and twists and turns.

As an example of what this looks like in practice, in our recent progress review for Logan Together, we looked at the progress they’d made in implementing the collective impact model as well as the progress made in some key intermediate outcome domains. So, how had they advanced in terms of community engagement, social innovation, improving resource flows and collaboration etc? There are plenty of tools like rubrics and indicators that we can use to assess these sorts of middle-level outcomes and early instances of impact (ahead of the longer- term results). The challenge is usually around narrowing them down and defining what success means for different phases, because there are so many domains to focus on in these types of initiatives – selecting just a few vital ones (that are phase relevant) is key to keeping the process manageable.

“And with the need evaluate for conditions for change, is the need to constantly build and check in on readiness to work for systems change.”

This goes hand in hand with capacity to work adaptively and in complexity. Making sure you have robust Measurement, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) systems and processes can be a good place to begin as a way of building the muscle for adaptive work.

You mentioned systems change is non-linear – how do you measure change when you don’t know what it’s going to look like or what to expect?

To address emergence you are going to need different types of measures that can uncover unplanned or unexpected changes in the system and help you make sense of them. This often means qualitative and dynamic methods, such as Most Significant Change, Outcomes Harvesting and Significant Instances of Policy and Systems Influence (SIPSI). These methods search for change, harvest and make sense. They do not predict ahead of time what the change will be, instead they throw out a broad net to catch changes in the system and make sense of them.

We’ve spoken a lot about process, but what about people, and the role evaluators have to play?

“I think that’s still one of the issues we’re still wrestling with – how do we support our teams, organisations and networks to dynamically and reactively learn? What leadership, culture, structures, power dynamics and resourcing are needed to enable the MEL to stick?”

Often in these approaches, we see the work, including the MEL, being held by the backbone team. For example, the government and other funders sit ‘above’ the initiative – rather than constantly at the table reflecting on how they are showing up and contributing as collaborators. To truly facilitate systems change, we need to build readiness and capacity for systems leadership across all parts of the system – including funders, who could bring other valuable knowledge and learning to the table.

There’s a lot of value in participatory approaches when it comes to evaluating place based and systems change initiatives. A couple of practical ideas that we’ve found effective:

1) Develop a safe culture of learning around the MEL work and the initiative, and have explicit learning questions as well as evaluation and measurement questions. This promotes real time sharing of insights and data, and supports bigger shared measurement efforts. Evaluation has technical as well as cultural aspects.

2) Set your MEL work up around a set of shared principles. Some of the principles for MEL we’ve seen to be effective and important for systems change MEL are around being:

You mentioned that evaluators, we have on an ongoing learning role – what are some of the things you’re still learning or wanting to learn more about?

I’m still wrestling with how to develop indicators of systems health. There is potentially another piece of the measurement puzzle where we have lead indicators to help us see whether we are on track to a more optimised system. There is an appetite to co-design these indicators of the system health with communities. In the environmental sector I was often taken by the notion of “systems health indicators”, for example platypus prefer clean water, so where you see them thriving it is a sign that the ecosystem is healthy. So I’m interested in what would be equivalent of signs of a healthy system in the social sector. It might be how the system is experienced by the community, whether they feel it is safer and healthier. That’s is one area I hope to work on more in the next year or so.

I think we have much more to learn about how we can decolonise evaluation so that methods and approaches are culturally safe and relevant, particularly with our First Nations partners. We are learning through our partnerships, such as with Blak Impact, that decolonising evaluation means honouring Traditional ways of knowing, being and doing and recognising that First Nations cultures and people were evaluators before First Contact. It is about a two-way learning and facilitation of non-First Nations learning, and involves holding traditional knowledge and Western knowledge to further goals for First Nations people.

With many of the initiatives we work with, we’re still in the process of learning from our First Nations and community partners how to work together in culturally safe ways so the voices of groups that are often not heard in evaluation are included and amplified. First Nations communities, Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Groups, families and children – how do we ensure these voices are heard and represented throughout the MEL cycle? It takes intention, time and resources for good processes and relationship building.

I think place-based approached can be an incredible opportunity to advance this, where we can contribute to knowledge and power sharing among First Nations and non-Indigenous communities through our MEL work, with the ultimate goal of supporting power-sharing, self-determination, and reconciliation.

For those looking to delve deeper into this topic, check out our Evaluating Systems Change and Place-Based Approaches course.

The Cook and the Chef – How Designers & Evaluators can Collaborate or...

The Cook and the Chef – How Designers & Evaluators can Collaborate or...