The world is moving under our feet. I am sure I am not the only person to feel it. Everyone is struggling to come to grips with how COVID-19 has changed our lives. I work in M&E within international development, and with the border closures, I cannot travel to work with partner organisations.

Even if I could travel, those partners are in emergency mode, responding to COVID-19 in the best way they can. Planned M&E activities are often put on the backburner for more pressing priorities.

When I have thought about the work they are doing, as well as the everyday heroism of nurses, doctors and cleaners, I have struggled at times with my own relevance as an M&E consultant in international development. How can I help during COVID-19?

In this blog, I want to share some of my initial thoughts on how M&E can help international development to respond to COVID-19. I say they are initial as they will evolve over the course of this pandemic. At Clear Horizon, we will continue to share and refine our thoughts on how M&E can support communities to respond, as well as adapt to the challenges and opportunities raised by this seismic change.

Supporting evidence-based decision-making

International development programs are delivering urgent materials such as Protective Personal Equipment (PPE) to partner countries or funding other organisations to do this. However, in the rush to deliver essential materials and services, setting up data systems that provide regular updates on activities, outputs, ongoing gaps and contextual changes are often neglected.

While understandable, setting up M&E systems to provide regular reporting is essential. Decision-making will be at best limited if it is not informed by evidence of what is happening on the ground.

For example, if we understand what programs/donors are funding, where and any ongoing gaps, we can better coordinate with other programs to ensure that we are not duplicating efforts. There is also an accountability element, as our work is often funded by the taxpayer. In a time where people are losing their jobs in record numbers, we have an obligation to report how their taxes are being spent.

We can learn from humanitarian responses on how to develop lean M&E systems. Examples include fortnightly situation reports which outline in one-to-two pages key results, next steps, and any relevant context changes.

There is also an opportunity to draw on digital technology to provide organisations with clearer oversight of their pandemic response. Online dashboards such as the ones we use through our Track2Change platform can provide organisations a close to real-time overview of where they are working, what they are delivering and key outcomes.

Driving learning and improvement

More importantly, M&E will help us to understand what works, in what contexts and for whom. We work in complex environments where there are multiple interventions working alongside one another, along with dynamic economic, political, cultural and environmental factors that interact with and influence these interventions. Non-experimental evaluation methods such as contribution analysis and process tracing help us to understand why an intervention may or may not work in certain contexts due to certain contributing factors, and thus what needs to be in place for this intervention to be effectively replicated elsewhere.

But M&E does not only support learning at set points in the program cycle, such as during a mid-term evaluation, but on an ongoing basis. For example, regular reflection points could be built into programming with program staff coming together, face-to-face or through online video conferencing. In these meetings, stakeholders can reflect on evidence collected in routine monitoring, as well as on rapid evaluative activities such as case-studies on successful or less-successful examples.

During these sessions, program M&E staff would facilitate program teams to reflect on this evidence to identify what is working well or not so well, why and what next. Ongoing and regular reflection also draws on the tacit knowledge of staff – that is, knowledge which arises from their experience – to inform program adaptation. This sort of knowledge is essential in dynamic and uncertain contexts where the pathway forward is not always clear and decisions may be more intuitive in nature.

Clarifying strategic intent

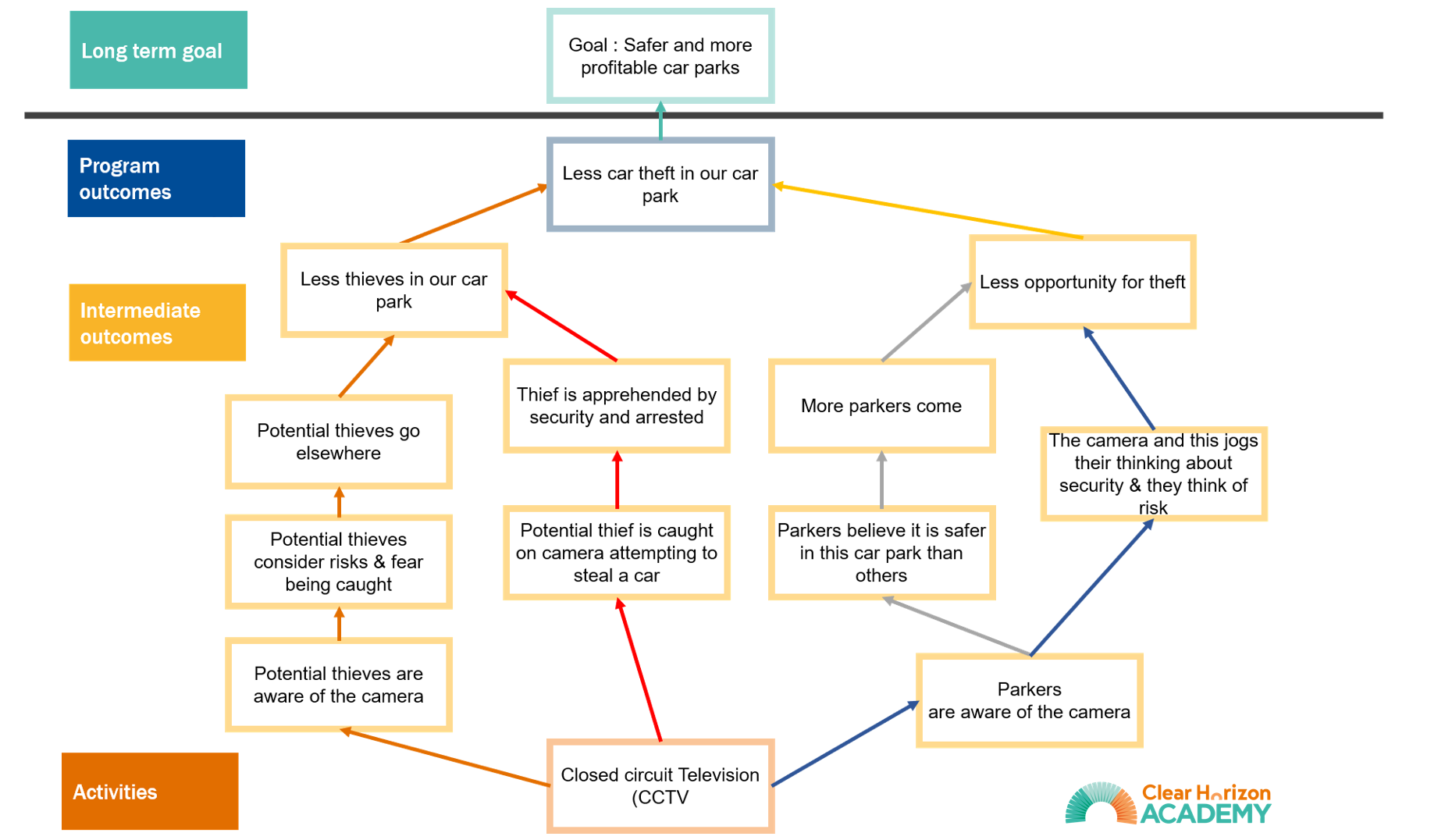

Thinking about your strategy is not necessarily at the top of your mind when responding to a pandemic. However, as the initial humanitarian phase of COVID-19 winds down, and we start to think about how to work in this new normal, program logic (or program theory/theory of change depending on your terminology) is a useful thinking tool for organisations.

Simply put, program logic helps organisations map out visually the pathways from their activities to the outcomes they seek to achieve. Program logic not only helps in the design of new programs to address COVID-19, but the repivoting of existing programs.

COVID-19 will require organisations to consider how they may have to adapt their activities and whether these may affect their programs’ outcomes. For example, an economic governance program may have to consider how to provide support to a partner government remotely and this may mean they have to lower their expectations of what is achievable. By articulating a program logic model, an organisation can then develop a shared understanding of their program’s strategic intent going forward.

You can, of course use logic to also map out and get clear about the COVID-19 response itself. For example, we used program logic to map out one country’s response to COVID-19 in order to identify what areas our client is working in and the outcomes they are contributing towards, such as improved clinical management and community awareness, so that they can monitor, evaluate and report on their progress.

Locally led development

This crisis poses an opportunity for local staff to have a larger role in evaluations. This not only builds local evaluation capacity, but enables local perspectives to have a greater voice.

Typically, international consultants fly in for a two-week in-country mission to collect data and then fly home and write the report. National consultants primarily support international consultants in on-ground data collection.

In Papua New Guinea, we are promoting a more collaborative process to M&E in which international and national consultants work together across the whole evaluation process from scoping, data collection, analysis and reporting. As national consultants are on the ground and better able to engage with key stakeholders, their insights and involvement are essential to ensuring that evaluation findings are practical and contextually appropriate.

But I think we should look for ways to go beyond this approach to one that has local staff driving the evaluation and us international consultants providing remote support when required. For example, we could provide remote on-call support throughout the evaluation process, as well as participate in key workshops and peer review evaluation outputs such as plans and reports.

This could be coupled with online capacity building for local staff that provides short and inexpensive modules on key evaluation topics. At Clear Horizon we are starting to think more about this sort of capacity building through our Clear Horizon Academy, which provides a range of M&E training courses including Introduction to Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning.